Yet another vibe shift with Sean Monahan

This week, I got a chance to chat with writer and K-HOLE co-founder Sean Monahan about his latest trend report for , Live Players. We talked about our collective dissatisfaction with social media, new rules of cultural production, and what it means to be a live player.

You're known for coining the term "vibe shift," but it has become so popular that its original meaning has been lost. What were you originally describing in 2021?

In that report, I talked about a return to scene culture, which was my focus even before I wrote about the vibe shift. This was before COVID. I discussed the resurgence of scenes as a response to cancel culture, where building your own community with like-minded friends allows you to bypass the social consequences of cancel culture.

Another prediction I made was that fewer people are interested in art, but there has been an explosion in the number of people writing indie fiction or small press novels. The younger generation seems to be more interested in literature than traditional arts.

Lastly, I hypothesized a comeback of rock music. These observations all point to a cultural shift influenced by previous internet eras, reacting to different platform incentives and a longing for the pre-social media era.

I can't take credit for the popularity of indie sleaze, but in the vibe shift report, I highlighted the resurgence of 2000s, Terry Richardson photography, and the Cobra Snake. Even those who claim to dislike nostalgia are participating to some extent. This was exemplified by the Celine show at the Wiltern in Los Angeles, where Iggy Pop and the Strokes performed and the small creative Los Angeles scene was invited.

In your report, you mentioned the strong interest in the early 2000s aesthetic, but there is also a lot of nostalgia 2013-2014 online. What do you think is the reason for this?

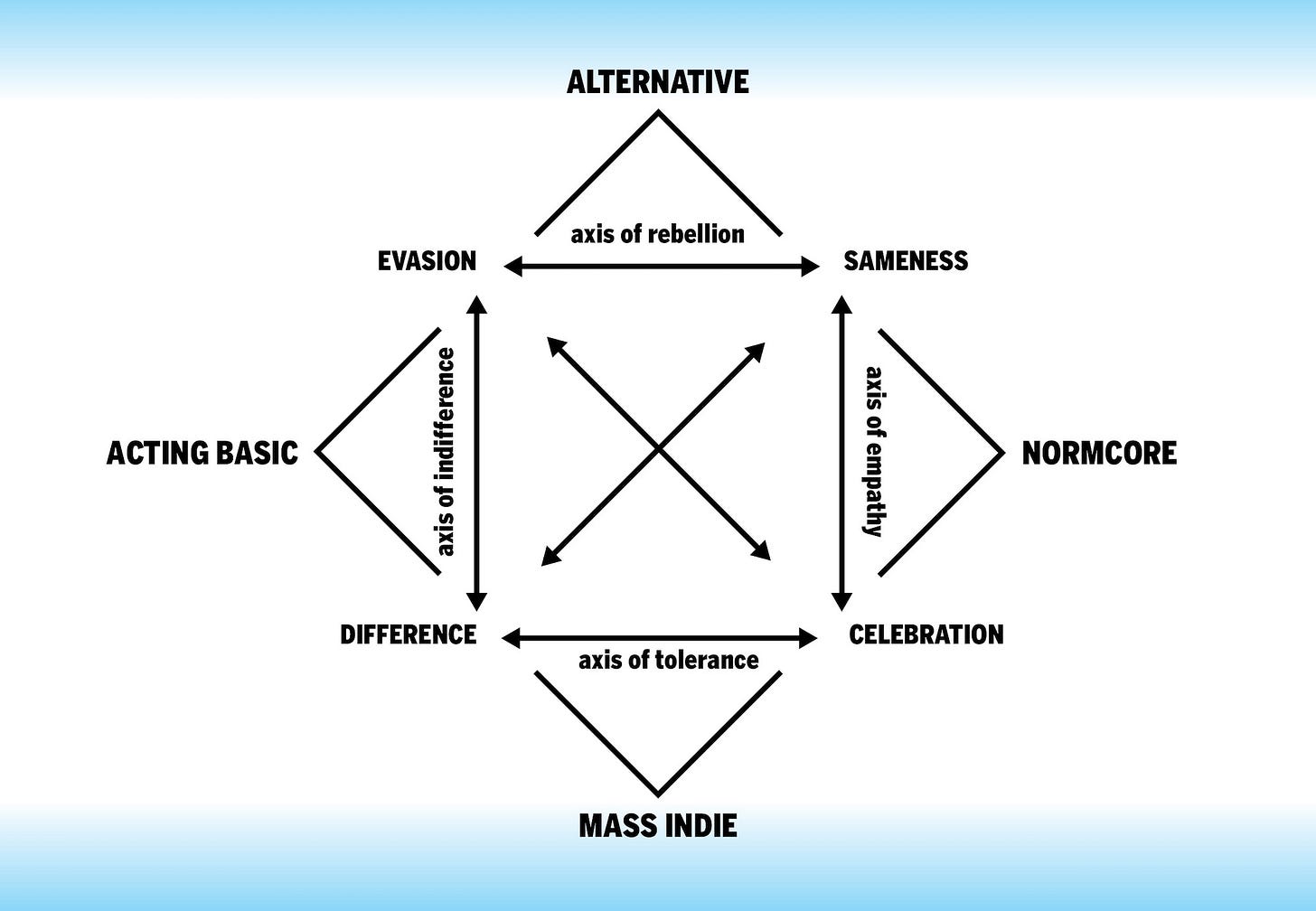

I recently had a conversation with a younger person about the timeline of indie sleaze. It seems that the perception of indie sleaze depends on a person's age. I understand indie sleaze as an art school and hipster aesthetic that emerged in the late 2000s. However, there are younger people who associate it with the mass cultural version of hipsterdom in the 2010s, influenced by Tumblr, Lana Del Rey, and Sky Ferreira. This was what we referred to as "mass indie" in one of the K-HOLE reports.

The perception of time depends on one's social class and proximity to cultural producers.

The further down the social ladder and the more one's consumption patterns are influenced by mass culture, the later they believe something happens. For example, normcore was a term that gained mass popularity in the United States around 2017-2018, even though the original paper was written in 2013. I recall having dinner with a buyer for Kohl's in Atlanta, and he said to me that normcore was really happening. It made me realize that living in New York City, surrounded by artists, designers, and musicians, can create a perception that things happen quickly. However, it takes about five years for trends to truly permeate the culture.

I think information is moving faster than ever, but cultural change is still pretty slow. And a lot of that just has to do with the fact that people who exist within a creative scene, as I mentioned in my new report, have a much higher novelty preference than your average consumer and are much more interested in constantly doing new and different things, whereas most people are hesitant about making big aesthetic statements

In your new report, you don't really talk about generations even though certain trends are definitely connected to specific age groups.

A lot of people don't like generational discourse, but I think there's something that's fundamentally true about people being marked by the era they grew up in and the kind of technology that was available. In the second part of my report, I'm going to address my thoughts on nostalgia and a generational approach a little bit more directly.

Looking back, I think my vibe shift report resonated so much with people because I wasn't trying to be mean about it, but I was calling millennials old. That was the experience of coming out of the pandemic — a lot of people went into it feeling pretty young. Now you're like, "Oh, wow, I'm really an adult." And also suddenly there are all these young Gen Z people with different cultural tastes who are treating the things that you did in your early 20s or teens as cool, fetishistic things from the past.

Another observation you make in your new report is about the disappearance of counterculture. Do you think there is a place for countercultural communities online? Or where can creative people work out new ideas?

I don't think there is such a place anymore, and there isn't really a coherent elite either. No one possesses the trifecta of financial capital, cultural capital, and political capital, i.e., social capital. I believe this is largely due to the fact that the tech industry doesn't value culture very much. They only want to support things that are optimized for the internet, and the internet is not particularly good at producing culture.

When we look back and evaluate some of the big promises and predictions about how tech platforms would change things, they don't always hold true. We are currently seeing this with generative AI. If someone had asked me earlier this year, I would have bet that there would be a best-selling novel written with Chat GPT by the end of the year, but clearly that didn't happen.

Many predictions about a massive explosion of creativity did not come to fruition, and I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that creative people are overwhelmed with social media today.

Yes, maintaining any kind of online presence requires a tremendous amount of work.

I ended up taking a break because going viral gives me writer's block, and because you start to feel trapped by your audience. You begin to anticipate what you should do to make small pieces of content perform better, but they don't necessarily add up to a whole. Social media has significantly changed many industries — creative individuals are now responsible for much more self-promotion.

The best practices to work with the algorithm and generate the most income are very limited, and I think many people get burnt out. And the audience becomes bored with others' content because it shouldn't be overproduced.

After I published my report, I didn't link to Samo Burja's essay, Live versus Dead Players, that I've discussed a lot in the last year with my friends from San Francisco. Burja lists people like Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and Sam Altman as live players. They are simultaneously feared and regarded as people who make things happen. And there are live players in culture as well — what makes them stand out is that they work against algorithmic expectations.

People in the tech industry are hesitant to admit that algorithms restrict cultural production. Some of the most meaningful changes are occurring within more traditional institutions, where individuals are paid to create things that may not be immediately profitable but are important in the long run. I don't believe Silicon Valley needs to function like cultural industries, but "discourse" on Twitter can serve as a substitute for those old institutions.

In your opinion, which institutions have successfully influenced the culture in recent years?

I believe Balenciaga has been successful, although they may be reaching the end. They have been an important cultural institution for the past 5-7 years since Demna Gvasalia joined. They have transformed how people dress by taking ideas from the post-internet era in downtown New York, popularizing them, and merging them with streetwear.

There is also a community surrounding the brand, consisting of people who have worked with Balenciaga or are friends with those who work for the brand. They have all contributed to what has become a significant cultural force over the past half-decade.

Has your approach to creating change changed in the last couple of years? When you started in 2013 with K-HOLE, you were one of the very few people producing anything in this format, and now there are dozens of Gen Z trend reporters and forecasters on TikTok, YouTube, and other platforms.

Yeah, trend reporting has become a content vertical in and of itself. I enjoy reading a lot of those things. What I do is a little bit different because I am just not so deeply interested in TikTok trends, and they're very ephemeral. This is how people end up missing the forest for the trees. They're constantly chasing memes, which are more like fads than trends. A lot of it just has to do with imprecise language. Some trends are so big, slow-moving, and transformative that it can feel a bit redundant to even address them.

I understand why people like reporting on micro trends, but I don't know how much meaning there is in them. Something like "girl dinner" — people come up with it to try to talk about culture and find new fun ways to describe the reality around them. Internet culture is difficult to talk about and has become more difficult to talk about because there are competing versions of events. And again, this goes back to the personalization algorithms.

I think I'm interested in talking about trends that are metacultural and influence how people behave and how people see themselves and see the world. It's less about the memes and more about the people posting them. Or in a recent dissatisfaction with social media and the influencer market. A big part of what my new report is about is people wanting to escape their online lives and become active participants in the real world. Especially in the U.S., everyone is realizing that things are in flux.