I'm back from a (prolonged) break. This newsletter turned one year old last fall, and I'm grateful for every person who is reading this.

In the last couple of months, I've been thinking a lot about both AI and creativity. In 2024, I joined Archetype AI as Head of Marketing to find the right language for the new technologies the team is pioneering. At the same time, I was reading The Artist's Way by Julia Cameron. I have been using AI tools for a long time (mostly for work); starting The Artist's Way and doing the exercises suggested by the author — most of them requiring only a pen and paper — made me think about the relationship between media we create with Claude and ChatGPT versus the art that Julia Cameron describes in her book.

Besides the huge impact this book had on so many practicing artists and on me personally, The Artist’s way highlights aspects of human creativity that explain some of the tensions between AI-generated text and imagery and pieces created by humans. I wanted to share some of the main observations from reading the book, plus add a couple of my favorite articles and videos on the subject.

The source of creativity

The first big distinction is the source of creativity. The main exercise that the author suggests is Morning Pages — writing down everything that comes to mind, stream of consciousness style for 20-30 minutes daily — to start each day. The second important pillar of Cameron’s method is going on weekly Artist's Dates — nurturing yourself by doing something that inspires your creativity.

According to The Artist’s Way, creativity comes from paying attention to your own inner life (Morning Pages) and the outer world (Artist's Dates). Cameron’s approach is about turning this embodied experience into a source of inspiration for your work. She writes:

The quality of life is in proportion, always, to the capacity for delight. The capacity for delight is the gift of paying attention. […] More than anything else, attention is an act of connection.

The Artist's Way was inspired by AA and other 12-step programs, and in addition to doing the exercises, the crucial step is accepting God or some form of divinity. This may be met with a lot of resistance by many, but The Artist's Way, Natalie Goldberg's Writing Down the Bones, and many other books — for example, Bird by Bird written by devout Christian Anne Lamott — are deeply rooted in their authors' spiritual practices. Here is how Cameron puts it:

Creativity requires faith. Faith requires that we relinquish control. This is frightening, and we resist it. Our resistance to our creativity is a form of self-destruction.

It's hard to accept some of the religious aspects of Cameron's book — I grew up among atheists and I feel like certain parts of The Artist's Way elicit a similar uneasy feeling that AA's religiosity provokes in some people. Yet when we consider the difference between AI-generated text, images, or music, and the same things made by humans, it's all about divinity or the lack of it. Human creativity seems to tap into something transcendent that AI cannot access.

This March, OpenAI introduced the ChatGPT-4o image generator and users started creating millions of images in the style of Studio Ghibli. As the Ghibli-inspired and AI-generated visuals portraying Trump, Elon Musk, and fentanyl dealers went viral, the clip of anime director Hayao Miyazaki resurfaced where he called AI "an insult to life itself." His reaction doesn't directly mention the divine source of creativity, but as he shares a story about a disabled friend, it's clear that his contempt for AI-generated animation comes from believing that it isn't rooted in any kind of lived experience and therefore lacks the human dimension that makes his works so memorable.

The process

Most exercises in The Artist's Way are designed to help the reader fall in love with the process of making art and detach from the result. Cameron's approach is all about finding a childlike innocence within yourself — picking up a notebook and searching for joy rather than aiming for a certain outcome. It's about hoping that putting pen to paper will propel you into the future, even if that future is very uncertain.

Remember that in order to recover as an artist, you must be willing to be a bad artist. Give yourself permission to be a beginner. By being willing to be a bad artist, you have a chance to be an artist, and perhaps, over time, a very good one. […] The process, not the product, will become your focus.

The way we think about the (creative) output of AI is different from this approach. Very often, we're thinking of the desired result and trying to reverse-engineer a prompt that would produce what we're looking for. We're focused on the productivity that the tool demands. The price of using Claude and ChatGPT is influenced by the number of requests the user sends and expected response times, and this creates pressure to get things right on the first try. It's hard to give yourself permission to fail or, as Cameron writes, "poke into what other people think of as dead ends" and acknowledge that these dead ends are necessary.

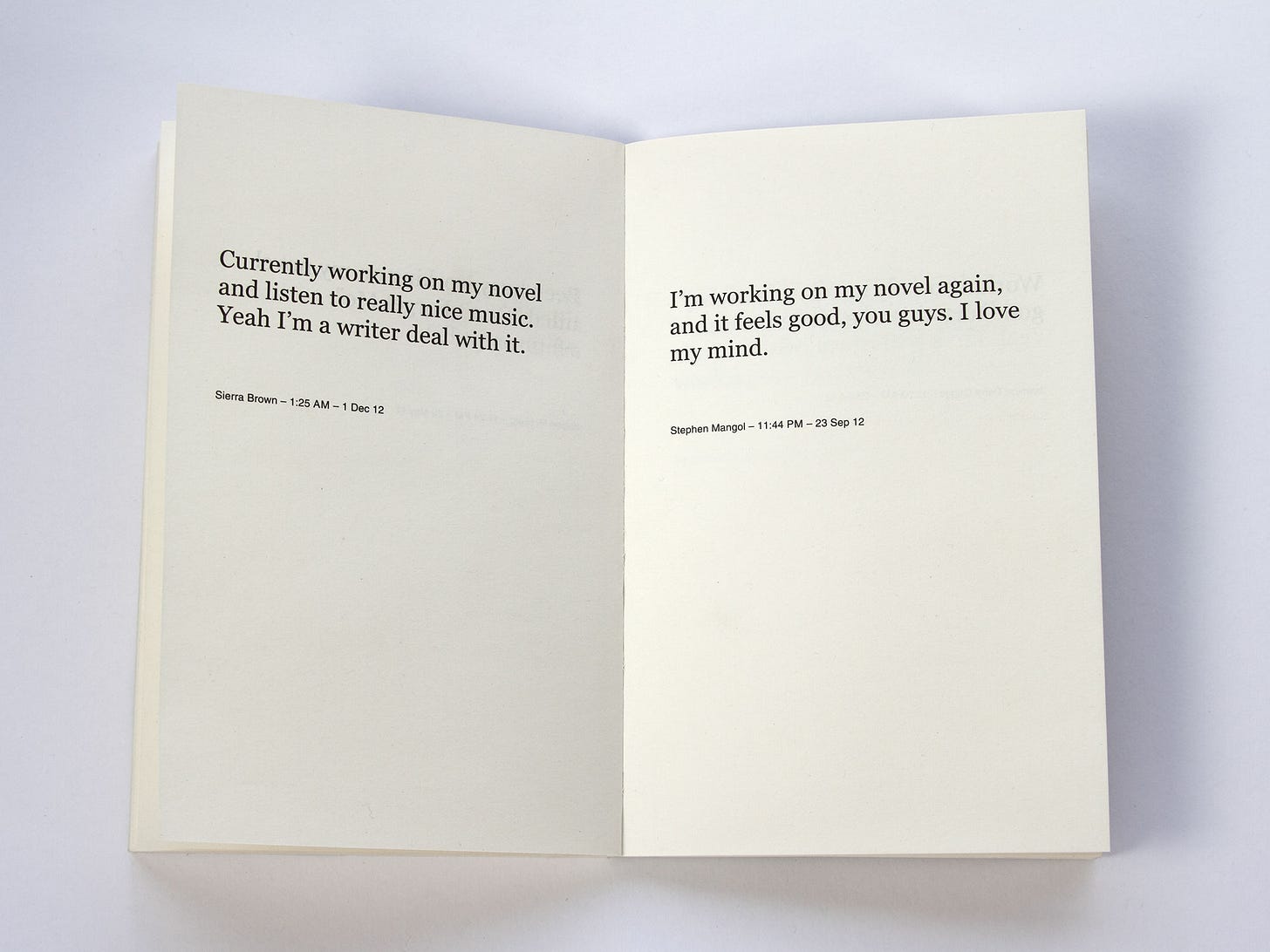

As an audience, we've also been falling in love with the process more and more — in modern fiction, film, and music the lines between the production and the finished product are blurring. In 2014, Cory Arcangel published Working on My Novel, a book that collected tweets mentioning an upcoming book. As an audience, we got used to artists sharing their work on social media or reflecting on the process after an album, a book, or a film is out. Musicians are live-tweeting from the studio, Sofia Coppola is publishing a book dedicated to her archive, and we’re delighted to learn all the references that inspired The White Lotus showrunner Mike White’s characters.

Writing and creating images with Claude and ChatGPT without any artistic intervention is anti-lore. There is no archive to create, there will never be an oral history about writing a novel or creating a screenplay with AI. We craft a prompt and get the result — you can build a practice and develop skills around it, but the speed at which you produce a finished project (or an iteration of it) doesn't allow for any connection to memory or spirituality.

The completed work of art

The popularity of ChatGPT and Claude has created a whole industry of educational posts, videos, and books on how to use these tools to augment your creative process, finally write a book that you always wanted to write, or at least create tolerable SEO and social posts for your employer or the startup you're building. Yet the truth is, LLMs can be very useful for many aspects of creative work but are not good at producing engaging copy. Sometimes it's less apparent, but there is a certain uncanny quality to AI-generated text. It makes you dizzy even if it's edited to eliminate words that LLMs overuse.

The output of LLMs is regurgitation of words from the past, of events that were already documented on the internet. To create something new, we need to describe familiar events with a new language or find simple words for something unusual. One of the creative writing exercises that Lamott mentions in her book (that has a lot of overlapping themes with The Artist’s Way) is describing something trivial — like a school lunch — and figuring out how to tell a new story or find an insight into one’s character through this simple description. The dizziness we feel when we read AI slop is the lack of this novelty, the smooth surface of everything that has been said before.

Many AI experts note that LLMs are successful at completing tasks where we know what a good outcome looks like — a PRD, a brief, meeting notes, but never a short story or a winning script or a really funny joke that doesn’t make you cringe. That requires courage and a leap of faith, and most importantly, lived experience — even if we put the spiritual aside, the best jokes (and the works of art) are about knowing yourself, and knowing your audience, and mixing all the little clues that the universe gives you in an unexpected way. In The Artist’s Way, Cameron included a quote from Agnes De Mille, “Living is a form of not being sure, not knowing what next or how. The moment you know how, you begin to die a little. The artist never entirely knows.”

Plus, more about creativity and AI:

Two critics — one AI-skeptical, the other AI-curious — discuss the merits of art made by machines by Jerry Saltz and and David Wallace-Wells

Am I Slop? Am I Agentic? Am I Earth? Identity in the Age of Neural Media by K Allado-McDowell

[VIDEO] Our Creative Relationship With AI Is Just Beginning by K Allado-McDowell

How I learned to stop worrying and love the slop by Ruby Justice Thelot

Such a great read 💡